Long before Boggsville, the Arkansas Valley was known to Native American peoples. Cheyenne and Arapahoe tribes were frequent visitors and Apache, Comanche, Kiowa and Navajo came too. The tribes found food, shelter and rich grasses. Buffalo were plentiful and they valued the beauty of the valley.

Hispanic explorers also knew the Arkansas Valley. Legend tells us conquistadors, likely from Coronado’s expedition, became lost and died without last rites, causing their souls to be lost in Purgatory. “Las animas que son perdidas en purgatorio” (“The souls who are lost in Purgatory”) lives on as the namesake for both the Purgatoire River and the town of Las Animas. The region south of the Arkansas River belonged first to Spain and then to Mexico until the United States seized it in the Mexican-American War of 1846.

Early North American explorers told of the area in their diaries. On November 15, 1806, Zebulon Pike described camping on the banks of the Purgatoire River and first sighting Pikes Peak when he was about two miles south of the Arkansas River. In 1820, Longs Peak explorer, Major Stephen Long, reported camping in the “valley of lost souls in purgatoire.” Trader and explorer, Jacob Fowler, wrote of camping at the mouth of the Purgatoire on November 13, 1821.

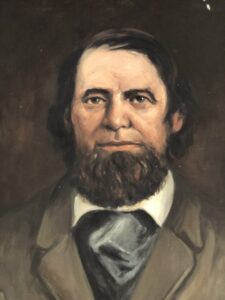

Thomas Oliver Boggs and his wife Rumalda Boggs, the first of Boggsville’s two founding families arrived in the Arkansas Valley in 1844. Boggs was the son of Missouri’s fifth governor, Lilburn W. Boggs and the great-grandson of Daniel Boone. For the next six years, Boggs worked as a trader for his uncles, William and Charles Bent at Bent’s Old Fort. He learned to speak Spanish and the languages of 11 Native American tribes. William Bent considered him one of the most useful and trustworthy plainsmen of the time.

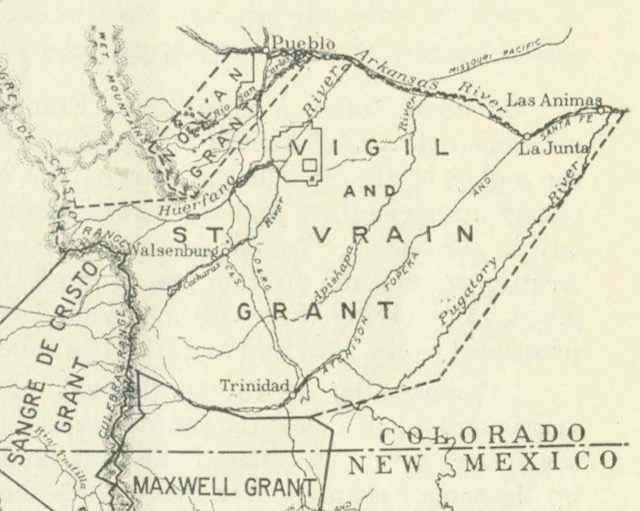

The Arkansas Valley impressed Boggs and he built his settlement there on land that was owned by his influential wife, Rumalda Luna. As a descendent of Cornelio Vigil, Rumalda had inherited 2,040 acres of land along the Purgatoire River just south of its convergence with the Arkansas River. Rumalda, who Boggs married in 1846, was the stepdaughter of Charles Bent, who was also the first territorial governor of New Mexico. One of her grandfathers was head of the Taos Customs House, the other a popular Santa Fe Trail merchant. Her great-uncle, Cornelio Vigil, was Taos’ mayor. Through her grandmother, Rumalda was part heiress to the giant Vigil and St. Vrain Spanish Land Grant of the early 1840s.

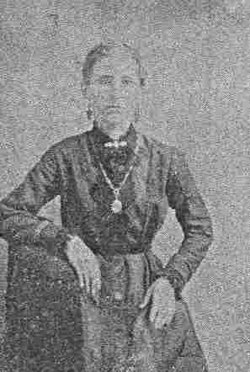

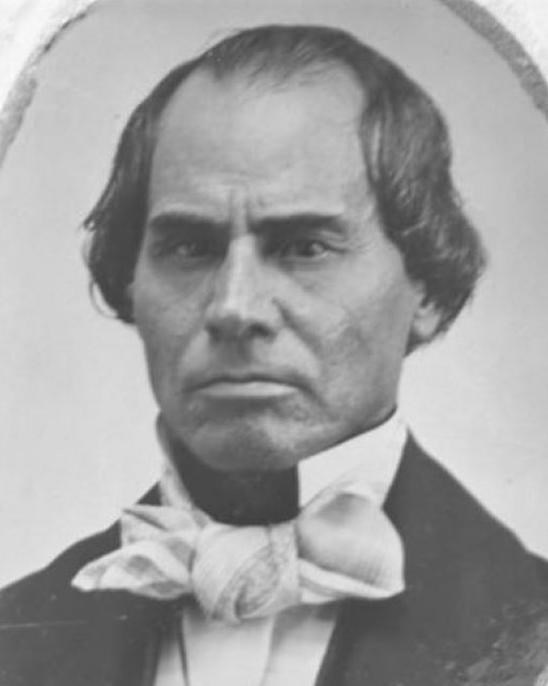

John Wesley Prowers, of the other founding family of Boggsville, was born in Missouri. A successful merchant and rancher, Prowers also married an influential woman whose land was situated near the Boggsville community. Prowers married Amache Ochinee in 1861. Amache was the daughter of a powerful Cheyenne sub-chief, Ochinee, or Lone Bear. Her family was at Sand Creek the morning Colonel John Chivington and his soldiers attacked. Her mother escaped, but Ochinee and other relatives were killed. As reparation, the United States government gave each survivor of those massacred at Sand Creek a 640-acre parcel of land. Amache, her mother and the Prowers’ two oldest daughters were all given tracts along the Arkansas River

A third influential female land owner was Josefa Jaramillo Carson, wife of Kit Carson. She too, was from a powerful Taos merchant family. Her father was Francisco Jaramillo, a respected trader, and her mother was Maria Apolonia Vigil. Both the Jaramillo and Vigil families were prominent in the Taos area. She also inherited a portion of the Vigil St. Vrain land grant. When she and Kit moved to Boggsville in 1867, her land was supposed to become the Carson ranch. Unfortunately, both the Carsons died within a month of each other in 1868 – Josefa from complications in childbirth and Kit from an aneurism.

The property owned by the women of Boggsville lay about three miles south of the confluence of the Arkansas and Purgatoire Rivers and about two miles south of present-day Las Animas. The Boggs family built a large adobe house. Its south-facing courtyard captured the winter sun, as was traditional of Rumalda’s Hispanic heritage. The Prowers family built a 14-room, two-story, U-shaped adobe house which faced east, reflecting Amache’s Cheyenne custom of honoring the rising sun. In addition to the family quarters, the Prowers house initially served as business offices, a stage stop, a mercantile and as a school for the community’s children.

Boggsville, located on a branch of the Santa Fe Trail, provided repairs, supplies and respite for travelers on the Santa Fe Trail. At its peak, there were over 20 structures in Boggsville, including a mercantile, blacksmith, stage stop and housing for residents and laborers as well as the businesses in the Prowers home. The first public school in southeastern Colorado was built just north of the Prowers’ house.

As Boggsville continued to prosper, residents dug an irrigation canal called the Tarbox Ditch. Seven miles long, it irrigated more than 1,000 acres, including the farms of Boggs, Prowers and Robert Bent (son of William). Their success spearheaded large-scale agriculture in southeastern Colorado.

Boggs and Prowers also pioneered expansive ranching operations. They raised horses, cattle and sheep. Prowers introduced European breeds of cattle (Hereford, Angus, and Shorthorn) and crossbred his cattle to produce stock that could survive harsh climates. His small 1860s herd eventually grew to about 10,000 head of cattle in the 1880s. The Boggs sheep herd numbered around 30,000 head – huge, even by today’s standards.

In 1867, the army moved Fort Lyon to its present site just a few miles northeast of Las Animas. The fort promised a major market for agricultural produce and livestock. The army bought nearly everything the farmers at Boggsville could produce.

When Bent County was established in 1870, it was a vast area of over 9,000 square miles – about six times larger than it is today. Boggsville served as the county seat from that fall until 1873. There were only 97 voting residents and county offices were located in the Prowers House. Thomas Boggs became the town’s first sheriff and he was elected to the territorial legislature the following year. John Prowers served in the territorial legislature in 1873 and the state legislature in 1880.

All too soon, the railroads came west. Tracks were laid to avoid established communities, allowing rail barons to make fortunes selling choice lands near their new stations. The rails reached the Arkansas Valley in 1873. The new city of West Las Animas became the center of business and Boggsville began its descent.

John Prowers relocated to West Las Animas where he built a new house, opened a mercantile and established the commission house and freight company of Prowers and Hough. Thomas Boggs remained in Boggsville, but when his wife’s land grant was challenged in 1877, the family moved to Clayton, New Mexico, out of frustration with the government bungling. Shortly after the grant was finally re-confirmed in 1883, Thomas and Rumalda Boggs sold their Boggsville ranch to John Lee for $1,200.

In a few short years, the people of Boggsville proved that one could live and prosper in an unforgiving environment with only “hostile Indians”, harsh weather and hardship. But Boggsville proved that diverse ethnic cultures could work together to conquer the elements and make progress for future generations. The Boggsville Historic Site stands as a monument to its success.